New and upgraded rail lines, in the Baltic States and Kaliningrad Oblast, were proposed here earlier. The proposals were integrated with each other, and with the older network. One proposal was a north-south high-speed rail line, Kaunas – Riga – Tallinn. Since then, the official Rail Baltica project has finalised its alignment, and it is no longer relevant to propose an alternative. On the other hand, the war in Ukraine has altered the logic of the project. This post reconsiders the earlier proposals, with suggestions for improving the official alignment.

The capacity of the rail network in the region is limited, and passenger services are minimal. Rail transport has low priority in the three Baltic states, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. They don’t cooperate with each other, or with their neighbours Belarus and Russia, and sometimes obstruct cross-border services. That was true long before the war. Lithuania was fined by the European Commission, for deliberately vandalising its own tracks, to block rail freight traffic into Latvia.

Not surprising, then, that the Rail Baltica project suffers from political hostility and interference. The alignment was determined by politics from the start, to avoid the Russian exclave Kaliningrad Oblast, which is the northern half of former East Prussia (Ostpreussen). Another example: the planned high-speed route from Vilnius to Warsaw makes a long detour. There was originally a direct line, but part of it is now in Belarus, and the three states can’t agree on re-opening. That would also require conversion to standard gauge, and the five states also can’t agree on gauge conversion policy. Another example: Latvia insisted on routing Rail Baltica through Riga airport, which will delay travellers between Estonia and Lithuania. These travellers will not be using Riga airport anyway, because all three countries protect their own national airports.

Then came the Ukraine war, which undermined the stated intention, to connect the Baltic states to the rest of the EU. The Rail Baltica alignment passes between Belarus and the Kaliningrad exclave. When it was planned, that was not a problem, because no hostile action was anticipated. But since then, Belarus has allowed Russia to use its territory for an invasion, and it might do that again. The unproblematic corridor from the EU to the Baltic states became a geopolitical flashpoint, the Suwałki Gap – a potential Russian corridor to Kaliningrad. Of course, that would mean war with Poland, but even if it was arranged peacefully, it would still destroy the concept of an internal EU link to the Baltic states.

For the present, it does not matter anyway, because the Polish government never took the line beyond Suwałki seriously. It was left as a single-track non-electrified route, with an indirect alignment via Šeštokai. In practice, the Polish refusal to improve the cross-border link, reduced Rail Baltica to a Kaunas – Riga – Tallinn line, with a few extra trains to Warsaw.

What kind of line?

The Rail Baltica project is not a standard high-speed line either. It will carry freight – serving three multimodal terminals, and the port east of Tallinn (Maardu). High-speed rail lines usually carry no freight, for good reasons. Slower freight trains obstruct fast trains, and they require an appropriate gradient, track, and structures.

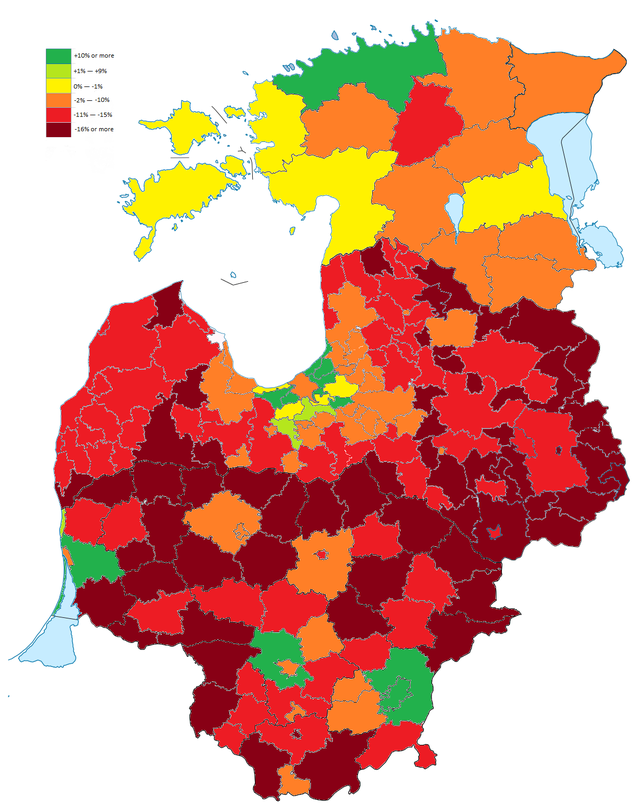

The Rail Baltic line will also have regional stations – possibly almost 40. Again there are some examples in other countries, but conditions there are very different. Regional population densities in the Baltic States are very low, and declining even further.

That means that the regional stations will serve very few people, too few to fill the trains. Some of the proposed stations are clearly absurd – Pasraučiai village, with 34 inhabitants, Kaisma village (123 inhabitants), and Urge village (144 inhabitants). No specific funding is available for these stations, which will cost about €2 million each, and the small local governments cannot afford them. If there is no external source of funding, then most of these stations will never be built.

Regional trains are only possible, because planned frequencies are very low. Trains between the main stations – Tallinn, Pärnu, Riga, and Kaunas – will run every two hours. A high-speed line cannot be economic with such frequencies – the HSL-2 in England is designed for trains every three minutes. The frequency of regional trains is not fixed yet, but it cannot be very high either, or the trains will be almost empty. This suggests that the ‘high-speed’ Rail Baltica is in fact primarily for freight, which would make it unique among high-speed lines. These freight trains will run at 120 km/h, on a line built for 250 km/h.

Deficiencies of the planned alignment

Kaunas, Riga, and Tallinn are approximately aligned north-south, and the Rail Baltica line generally follows this route. The alignment is not a straight line at local level, however. It curves continuously, partly due to environmental constraints. Most of it does not follow existing infrastructure.

At three points, there are major flaws in the alignment north of Kaunas. After leaving the built-up area of Kaunas, the line turns toward Panevėžys (population 95 000). Instead of entering that city, however, it turns west, to pass though open country. A new north-south line through Panevėžys is difficult, because the existing rail line run east-west. So instead, there will be an interchange station, where the new line crosses the Šiauliai – Panevėžys line. Experience in France shows that stations in open fields don’t serve the surrounding region, even if they cross an existing rail line.

The design error at Panevėžys can be corrected, by adding a new standard gauge line into the center from the west. It can largely follow the bypass (A17), and join the existing alignment about 3 km east of the station. It is not a perfect solution, but it would allow a high-speed Panevėžys – Kaunas shuttle service.

The second major design flaw is the approach to Riga. In fact Rail Baltica has a double alignment at Riga, with a line through the city, and a bypass line. However, the new line through Riga will turn west, then follow the ring motorway to the airport, and then turn back toward the central station, alongside the existing Jūrmala line.

It is relatively easy to correct this design error, by building a link to the existing Jelgava – Riga alignment near Tiraine, with extra standard gauge tracks into Riga. The two routes join at Tornakalns, close to the main station. The new link alignment would be about 15-20 km long, with about 8 km alongside existing tracks.

North of Riga station, the planned alignment could be improved by building new standard gauge tracks, alongside the exiting line through Garkalne. This alignment starts with two L-curves, but is almost straight, after passing Jugla.

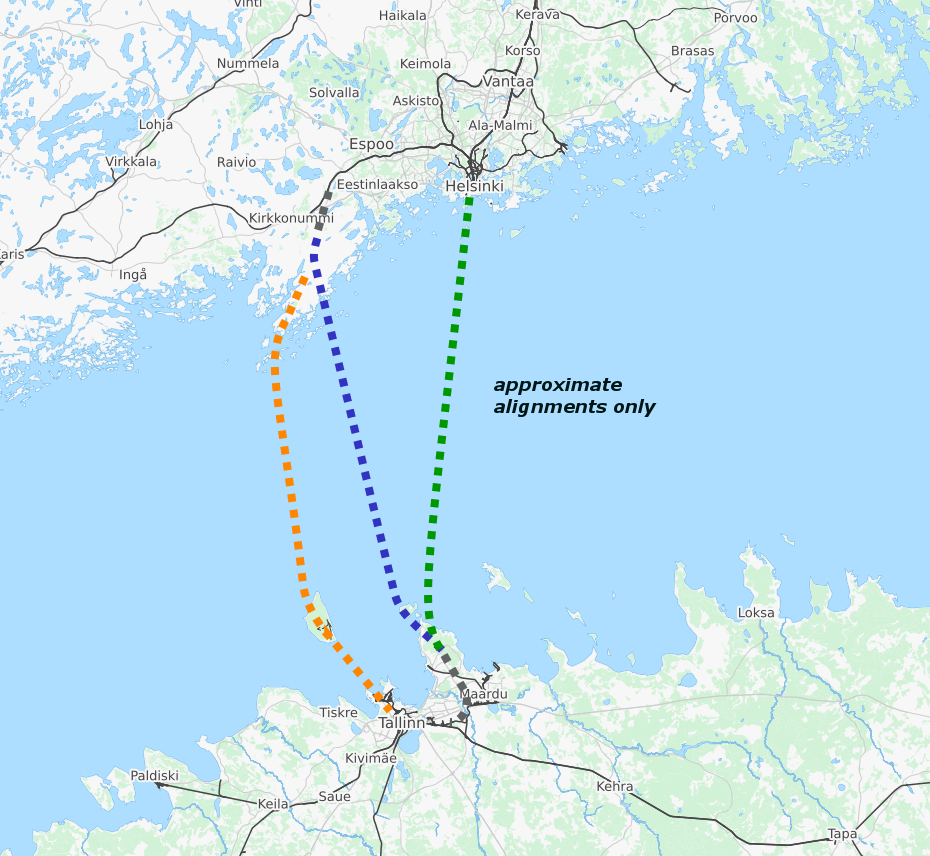

North of Riga, the planned route roughly follows the coast to Pärnu in Estonia, and from there to Tallinn. The third major design flaw is on the approach to Tallinn. The new line does not follow the logical south-north route, alongside exiting lines, but uses a semi-circular route to enter Tallinn from the east. Apparently, the freight link to the port at Maardu was more important, than passenger access to Tallinn. A possible tunnel to Helsinki cannot justify the diversion: it is not even clear, if a tunnel will run east of Tallinn. In any case, Rail Baltica trains will terminate at a new station at Ülemiste, at the edge of Tallinn. Passengers must change to local trains, to reach the city centre.

There is no easy fix here. It would however be possible to build a new line from the south, following existing tracks, from near Saku. It could terminate at the existing Tallinn central station, and include a connection to Ülemiste, if necessary.

Apart from these major corrections, it might be possible to correct other definities of the the Rail Baltica project, such as the lack of connection with local rail services, and no planning for conversion of Russian gauge railways. The general principle suggested here earlier, was to retain the east-west lines in Latvia and Estonia at Russian gauge, and convert most north-south lines to standard gauge, with most of the Lithuanian network converted.

Line from Warsaw

Gauge conversion is also an issue on the route from Warsaw to Kaunas. The present low-quality compromise uses either mixed-gauge single track, or two separate tracks. This is generally unnecessary, as there is no reason for Russian gauge tracks south of Kazlu Ruda, about 40 km from Kaunas on the Kaliningrad line. In fact, the logical option is to convert the entire Kaliningrad – Kaunas line to standard gauge – as most of it was until 1945. That is politically unacceptable at present, because the line links Russia to a Russian exclave, but this blog ignores political constraints anyway.

If the existing line through Šeštokai was standard gauge, the real problem would be apparent – no political will to improve a low-quality line. At least in Poland – on the Lithuanian side, there are plans for a new link line, passing Marijampolė. That is a logical route, following the main road toward Suwałki. On the Polish side, however, there is certainly no prospect of a new high-speed line from Suwałki to Warsaw, which is the logical extension of any Tallinn – Riga – Kaunas HSL.

An approximate alignment for a Suwałki HSL was posted here earlier, but that post is out of date. In summary, the new HSL would start with a new tunnel in Warsaw, to connect the cross-city main line to Polish line 6, formerly the Warsaw – Vilnius – St. Petersburg line (1862). The HSL would run alongside Line 6, and diverge about 60 km from Warsaw, turning north-northeast toward Łomża. Because the centre is on higher ground, the new line can pass through the city, using the existing terminal station and a new tunnel.

The HSL would bypass Ełk, following the Via Baltica road, but some trains could serve Ełk, by leaving and rejoining the HSL. The HSL would then run north-east to Suwałki, again following the Via Baltica rather than the old rail alignments. The current terminal station in Suwałki (population 69 000) can be replaced by a new through station, using existing rail alignments on the eastern side of the centre.

From Suwałki, the HSL would follow the old main road to the Polish border, where is would join the proposed new line to Kaunas, with one stop at Marijampolė. The new HSL would therefore have only three intermediate stations – Łomża, Suwałki, and Marijampolė.

Berlin – Kaunas route

If we ignore the geopolitical issues, the most logical route from Western Europe to the Baltic States, is via the old German main line. The Preussische Ostbahn to East Prussia extended 600 km, from Berlin Ostbahnhof to Königsberg. East Prussia was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union in 1945, but if that alignment was still German territory, then trains from Berlin to Kaunas would probably run via Königsberg. That is still an option, because a new standard-gauge HSL, from Berlin to Kaunas via Kaliningrad, could connect to the Rail Baltica alignment at Kaunas.

When East Prussia was still German, the trains from Berlin continued to Memel, now Klaipeda. That was the last German city, at the ‘far end’ of the Reich. There was no main rail line from Königsberg to Riga, which was historically better connected to Moscow. (A secondary line was later built via Radviliškis junction, near Šiauliai.) A new high-speed route from Kaliningrad to Riga, via Šiauliai and Jelgava, was proposed here earlier. However, assuming completion of the Rail Baltica line, the route via Kaunas seems a good alternative.

There are other possible routes to the Baltic States. Parallel to the Berlin – Königsberg route, there was also a route Berlin – Posen – Thorn – Allenstein – Insterburg – Tilsit – Memel. Of these seven cities, only one is still in Germany. Upgrading of this line, to the standards of the German Ausbaustrecken, was proposed here earlier.

The new route would be Berlin – Poznań – Toruń – Olsztyn – Chernyakhovsk – Sovetsk – Klaipeda, connecting to a possible new line to Liepaja. As with the Berlin – Königsberg line, this line could also carry trains to Kaunas, which can join the Rail Baltica line to Riga.

So even if the present route of Rail Baltica has many defects, most could be corrected in the longer term, as part of a European HSL program. Again, this simply ignores the present geopolitical issues, and the self-interest of national governments.

Helsinki tunnel

The Rail Baltic project is often presented as access to an undersea rail tunnel, linking Tallinn to Helsinki. In fact, this tunnel is not a precondition for the project, and not a passenger route to Western Europe. Despite much public interest, there are no serious plans at the moment, for this expensive project.

Several route options have been proposed, some of them by private investors. If there is a single long tunnel, then it might start east of central Tallinn, on the Viims peninsula, which is already served by the Maardu port line. If the tunnel is constructed from island to island, possibly via Naissaar island, then it might start west of Tallinn, even through the total route is longer. Similarly, on the other side, an indirect route to central Helsinki might be easier to construct.

The route, from central Tallinn to central Helsinki, would be about 100 km long. The absolute minimum is the great circle distance between the two central stations, which is 82 km. That is not a ‘short trip’. The route from Berlin to Helsinki is about 1400 km, beyond the generally accepted range for displacement of air traffic to high-speed rail.

So even with a Tallinn to Helsinki tunnel, Rail Baltica is not a ‘shortcut to western Europe’ from Finland. Most passenger traffic through this tunnel will be Finland – Estonia traffic, just as with the existing ferries. The issue of gauge conversion must be seen in that context: it is not absolutely necessary to convert the entire Finnish rail network. Theoretically, the tunnel should have mixed-gauge tracks for maximum flexibility, but that is not compatible with high speeds – trains cannot be centred under the catenary. So in practice, it might be more logical to use Russian gauge for a tunnel between two Russian-gauge countries. In that case, Ülemiste would be the interchange station. The balance is different for freight, however, because the long route to western Europe is still faster than a ship. It might therefore be preferable to construct a separate single-track mixed-gauge tunnel, for freight trains only.